Navigating Nullable Types in Scala 3: Understanding T | Null and Its Trade-offs

A Story of Vars, Nulls, and Broken Dreams

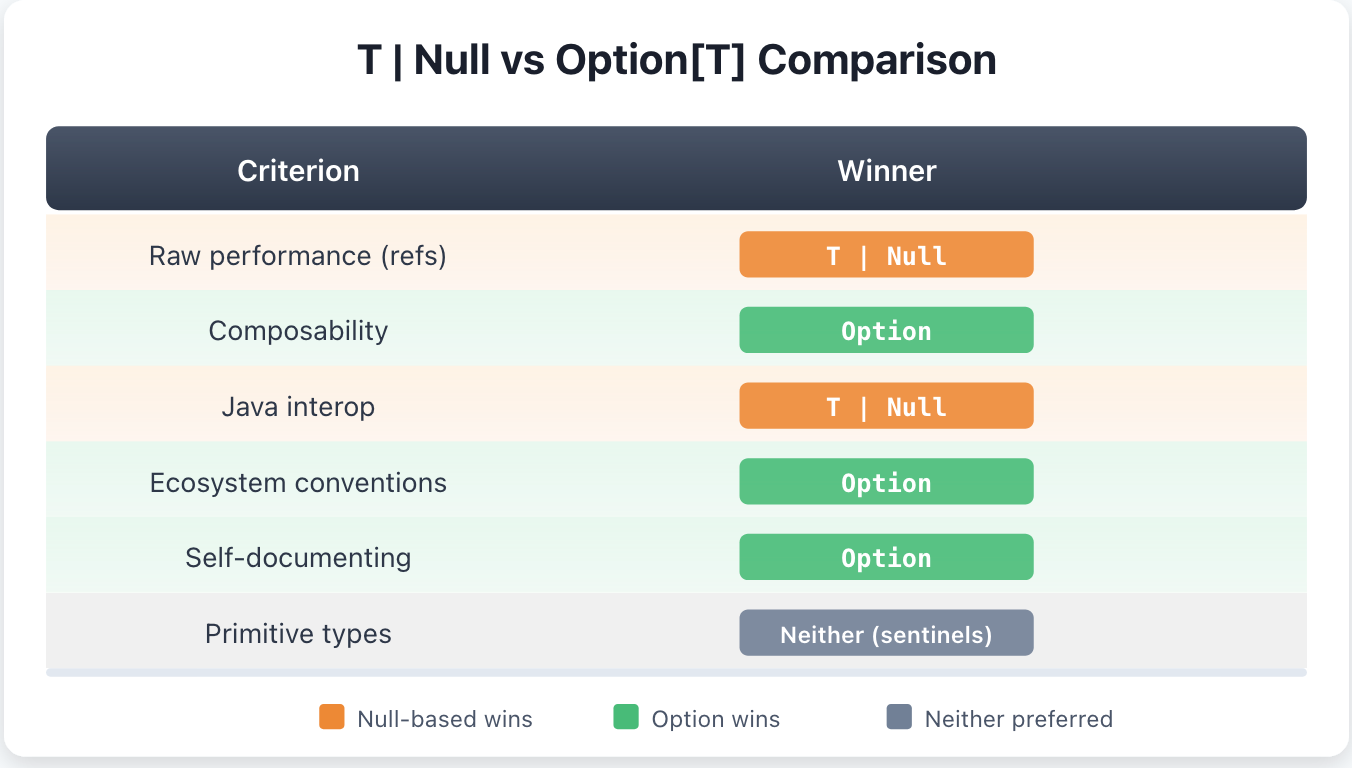

Scala 3 introduced explicit nulls, a compiler feature that brings null safety to the language through union types. When you enable the -Yexplicit-nulls flag, the type system distinguishes between types that can hold null and those that cannot. A variable declared as String | Null explicitly indicates that it might contain either a string or null. This approach differs fundamentally from Option[T], and understanding when to use each is essential for writing both safe and performant Scala code.

A recent thread on the Scala Users forum raised a deceptively simple question that revealed deeper complexities in Scala 3’s type system. A developer was porting performance-critical code from another language and wanted to use mutable variables with explicit null safety. The goal seemed straightforward: combine the performance benefits of var with the safety guarantees of Scala 3’s explicit nulls feature. What followed was a series of compilation errors that exposed fundamental limitations in how nullable union types interact with common programming patterns.

The original poster presented a minimal example involving an integer variable typed as Int | Null. When context made it clear that the variable held a non-null value, they wanted to perform a simple decrement operation. Every intuitive approach failed. Direct compound assignment did not compile. Using the .nn not-null assertion method did not help. Even wrapping the operation in an explicit null check, which would enable flow typing in many other contexts, still resulted in a compilation error. The only working solution was verbose explicit reassignment.

Wojciech Mazur, a contributor to the Scala compiler, responded with important context. He suggested opening an issue on the Scala 3 GitHub repository to bring the limitation directly to the compiler team’s attention. He also raised a crucial performance consideration that the original poster may not have anticipated: using Int | Null actually defeats performance goals because primitive integers must be boxed to java.lang.Integer whenever null is a possibility. The discussion then broadened to include reference types, where the same flow typing limitations apply but without the boxing penalty. This exchange illuminated not just a specific compiler limitation but a broader set of trade-offs that Scala developers must navigate when choosing between nullable types and Option.

The Compound Assignment Problem

A recent discussion in the Scala Users group highlighted an unexpected limitation when working with nullable types. A developer attempting to port performance-critical code from another language encountered compilation errors when using compound assignment operators with nullable variables. Consider the following code that demonstrates the issue.

//> using options -Yexplicit-nulls

var x: Int | Null = null

x = 42

x -= 1 // Does not compileThe compound assignment x -= 1 fails because it desugars to x = x - 1, and the union type Int | Null does not have a subtraction method. Only Int supports arithmetic operations, not the union type that includes Null. The natural instinct is to use the .nn extension method, which asserts that a value is not null and returns the underlying type. However, this approach also fails.

x.nn -= 1 // Does not compile: reassignment to valThe .nn method returns a value, not a reference. Writing x.nn -= 1 is semantically equivalent to trying to assign to 41 -= 1, which makes no sense. You cannot reassign to a computed value.

Flow Typing Limitations

Perhaps the most surprising failure occurs when using a null check. In many languages with flow typing, checking that a variable is not null narrows its type within the conditional block. Scala 3 does support flow typing for explicit nulls, but it has significant limitations with mutable variables.

if (x != null) {

x -= 1 // Still does not compile

}Even within the guarded block, the compiler refuses to narrow the type of x from Int | Null to Int. The reason relates to the fundamental nature of mutable state. Between the null check and the subsequent usage, another thread could reassign x. A method call with side effects could modify x through a captured reference. The compiler cannot safely assume that the variable remains non-null just because it was checked.

This limitation extends to assignment-based reasoning as well. The compiler does not perform definite assignment analysis that would allow it to narrow types after assignments.

var buf: List[Int] | Null = null

buf = List(0)

buf ::= List(1, 2, 3) // Error: value ::= is not a member of List[Int] | Null

Even though buf was just assigned a non-null value on the previous line, the compiler still considers it to have type List[Int] | Null. Implementing sound flow typing for mutable variables would require escape analysis to determine whether the variable could be modified through aliases or closures.

Flexible Types and Java Interoperability

The Scala 3 documentation on explicit nulls introduces a concept called flexible types, designed to smooth the interaction between Scala’s null-safe type system and Java’s ubiquitous use of implicit nullability. Understanding flexible types requires grappling with some notation that initially appears contradictory.

The Interop Challenge

Java methods routinely accept and return values that might be null, but Java’s type system provides no static indication of this. When Scala code calls a Java method returning String, should the result be typed as String (potentially unsound) or String | Null (safe but cumbersome)? Neither choice is ideal. Treating all Java references as nullable forces developers to write defensive code even when they know a particular API never returns null. Treating them as non-nullable silently introduces unsoundness.

Flexible types offer a middle path inspired by Kotlin’s platform types. When a Java method declares a return type of String, Scala 3 with explicit nulls represents it internally as String?, a flexible type that can be treated as either nullable or non-nullable depending on context.

The Puzzling Bounds

The documentation states that flexible types have bounds written as T | Null <: T? <: T. Reading this using standard subtyping interpretation creates confusion. If T | Null is a subtype of T?, and T? is a subtype of T, then by transitivity T | Null would be a subtype of T. But that contradicts the entire premise of explicit nulls, where Null is explicitly not a subtype of reference types. The documentation then shows examples that seem to contradict even this reading.

// Java class J with method: public String g() { return ""; }

val y1: String = j.g() // Assigning String? to String

val y2: String | Null = j.g() // Assigning String? to String | NullBoth assignments compile successfully. For the first assignment to work, we need String? <: String. For the second, we need String? <: String | Null. But the stated bounds include String | Null <: String?, which appears to be the opposite relationship.

Resolving the Apparent Contradiction

The key insight is that flexible types do not participate in standard subtyping with its transitive properties. The notation T | Null <: T? <: T should be read not as defining a position in the type hierarchy, but as describing the contextual behavior of the compiler!!! Now, that is a mouthful! A flexible type T? is treated as assignable in all the following scenarios.

// Values flowing INTO flexible type positions

j.f(x1) // String to String? works

j.f(x2) // String | Null to String? works

j.f(null) // Null to String? works

// Values flowing OUT OF flexible type positions

val y1: String = j.g() // String? to String works

val y2: String | Null = j.g() // String? to String | Null works

The compiler essentially allows T? to be compatible with both T and T | Null in both directions. This bidirectional flexibility is what makes the type “flexible” rather than occupying a fixed position in the subtype lattice.

Understanding Flexible Type Bounds in Depth

Let’s get back to this confusing notation T | Null <: T? <: T that looks like standard type bounds, but interpreting it through the lens of conventional subtyping leads to immediate brain freeze. To understand what the Scala designers actually mean, we need to examine what type bounds normally signify and why flexible types require a different mental model.

How Type Bounds Normally Work

In Scala’s type system, when we write bounds on an abstract type, we are specifying its position in the subtype lattice. Consider a standard bounded abstract type.

trait Container {

type Element >: Nothing <: AnyRef

}This declaration means that whatever concrete type Element becomes, it must satisfy two constraints: Nothing must be a subtype of Element, and Element must be a subtype of AnyRef. The abstract type occupies some position in the lattice between these bounds, and crucially, subtyping remains transitive through this position.

If we have A <: Element and Element <: B, we can conclude A <: B. The abstract type, despite being unknown, participates fully in the normal subtyping rules.

The Transitivity Problem

Now consider what happens if we apply this interpretation to flexible types with bounds T | Null <: T? <: T. Standard subtyping is transitive. If A <: B and B <: C, then A <: C. Applying this to the flexible type bounds gives us a logical chain.

Given: T | Null <: T?

Given: T? <: T

By transitivity: T | Null <: TBut this conclusion directly contradicts the foundation of explicit nulls. The entire feature exists because Null is not a subtype of reference types. If String | Null <: String held, we could assign null to any String variable, defeating the purpose of the feature entirely. Something in our interpretation must be wrong.

What the Notation Actually Describes

The bounds notation for flexible types describes compiler behavior at assignment boundaries, not a position in the subtype lattice. When the compiler encounters a flexible type T? in a particular context, it makes a decision about how to treat it based on what the code is trying to do. When a flexible type appears as the source of an assignment, the compiler asks whether the target type is compatible. Both of these assignments succeed.

val x: String = flexibleValue // T? flowing to T

val y: String | Null = flexibleValue // T? flowing to T | NullThe first assignment treats the flexible type as if it were T. The second treats it as if it were T | Null. The compiler permits both because flexible types are designed to defer the nullability decision to the point of use. When a flexible type appears as the target of an assignment, the compiler similarly accepts multiple source types.

def javaMethod(s: String?): Unit = ???

javaMethod(nonNullString) // T flowing to T?

javaMethod(nullableString) // T | Null flowing to T?

javaMethod(null) // Null flowing to T?All three calls compile because the flexible parameter type accepts values from anywhere in the nullability spectrum.

A Non-Transitive Compatibility Relation

The crucial insight is that flexible types introduce a compatibility relation that is not transitive. We can represent the compiler’s behavior as follows.

T | Null ~~> T? (T | Null is compatible with T?)

T? ~~> T (T? is compatible with T)

T | Null ~~> T (does NOT follow)The squiggly arrow represents “can be assigned to” in the presence of flexible types, which is different from the standard subtype relation. This compatibility relation deliberately breaks transitivity at the flexible type boundary.

You can think of the flexible type as a one-way valve that permits flow in both directions but does not connect its inputs to each other. Values can flow from T | Null into T?. Values can flow from T? into T. But values cannot flow from T | Null into T just because both are compatible with T?.

Why the Misleading Notation?

The documentation uses subtype notation <: because it is familiar and approximately captures the intuition. The bounds express that T? “acts like a supertype of T | Null“ in some contexts and “acts like a subtype of T“ in others. But this is a pragmatic description of compiler behavior, not a formal statement about the type lattice. A more precise notation might use different symbols for the two directions.

T | Null <: T? (for parameter positions, contravariant contexts)

T? <: T | Null (for return positions, covariant contexts)

T? <: T (when assigned to non-nullable target)

T <: T? (when non-nullable assigned to flexible target)But listing all four relationships would be verbose and still potentially confusing. The single expression T | Null <: T? <: T is a compact, if imprecise, way of saying “T? is compatible with everything in the range from T | Null to T.”

Implementation Perspective

From the compiler’s perspective, a flexible type is a special form that triggers relaxed type checking at Java interop boundaries. When comparing types for assignment compatibility, the compiler has special rules that fire when one side is a flexible type. The pseudocode for the compatibility check might look something like the following.

def isCompatible(source: Type, target: Type): Boolean =

if target.isFlexible then

// Flexible targets accept anything from Null to T

isSubtype(source, target.upperBound | Null)

else if source.isFlexible then

// Flexible sources can flow to T or T | Null

isSubtype(source.lowerBound, target) ||

isSubtype(source.upperBound | Null, target)

else

// Normal subtyping

isSubtype(source, target)This is a simplification, but it illustrates how flexible types receive special treatment rather than participating in normal subtype transitivity.

The Design Trade-off

Flexible types represent a deliberate choice to sacrifice type-theoretic purity for practical usability. A pure approach would force every Java method result to be typed as T | Null and require explicit handling. This would be sound but tedious, especially when working extensively with Java libraries whose null behavior is well understood.

By introducing a “soft” boundary at Java interop points, Scala allows developers to make local decisions about null handling. The cost is that the type system provides no guarantees at these boundaries. The benefit is that code can be gradually migrated to full null safety, and experienced developers can avoid ceremony when they have external knowledge about a Java API’s behavior.

The notation T | Null <: T? <: T is best understood as shorthand for this policy: “at flexible type boundaries, the compiler accepts assignments that would normally require explicit null handling, transferring responsibility for null safety from the type system to the developer.”